Australia has plenty of bad taxes. A particularly bad one is the luxury car tax (LCT), which John Howard implemented in 2000 as part of the GST package, and Kevin Rudd increased from 25% to 33% of the value of the vehicle above the threshold in 2008.

At the time, the federal government hit all goods with a wholesale sales tax of 22%, with “luxury” vehicles slugged at a rate of 45%. The Howard government argued that the tax was simply a way to ensure that “luxury cars fall in price only by the same amount as a car just below the luxury threshold”.

Why did the government tax luxury cars more than regular cars? Officially it was as a sort of Robin Hood, progressive tax that only hit the well-to-do. But really, it was to protect domestic car manufacturers through a politically-palatable mechanism: by targeting only luxury vehicles, it created concentrated benefits for local producers (e.g. Holden) while diffusing costs across a small and dispersed group of consumers—all without violating World Trade Organisation rules that prohibit taxing domestic and foreign producers differently.

But today the protectionist argument isn’t even there because not only does Australia have no domestic luxury car market, it has no domestic car market at all. Back in 2011, a group of economists concluded that:

“Based on economic theory and the political economics surrounding the issue, it is clear that the LCT is primarily a redistributionary tax that takes from the relatively wealthy few and gives to the not-so-wealthy many, albeit in a very inefficient manner. While it is far from being the ‘Robin Hood’ of taxes (take from the rich and give to the poor for the unambiguous good of society), it is accepted by a largely silent majority of Australians and opposed by a noisy few.”

The LCT is a narrow, discriminatory tax that reduces consumer welfare, creates economic inefficiency, and therefore causes significant deadweight losses for society. As the Henry Review wrote back in 2010:

“In the current Australian context, a tax on luxury cars is not a desirable means of raising revenue. It discriminates against a particular group of people because of their tastes. It is not an effective way of redistributing income from rich to poor. Its design is complex and becoming more complex over time.”

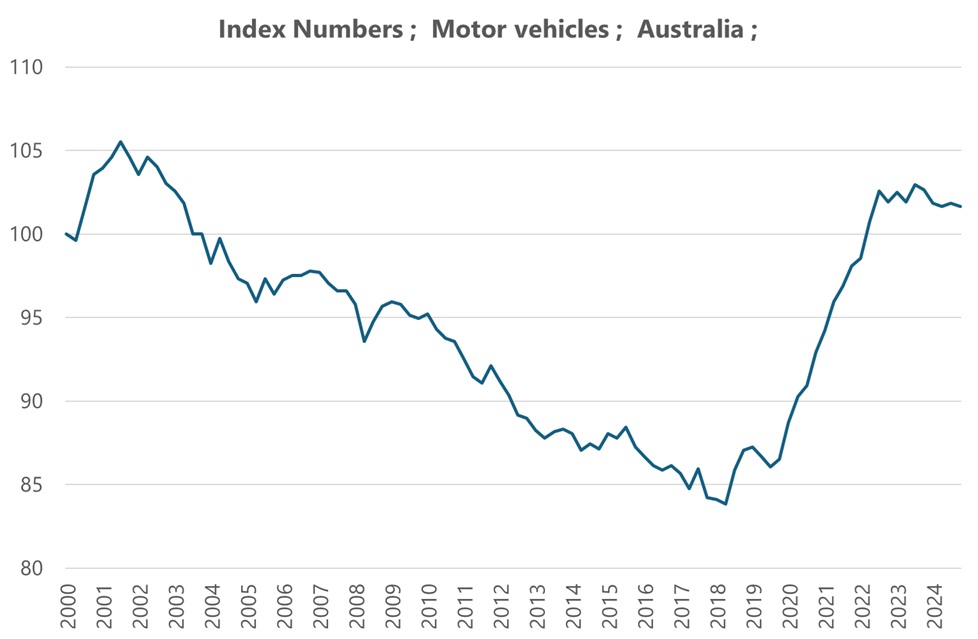

The LCT has caught more people over time because its threshold is indexed only to the motor vehicle component of the Consumer Price Index, which has risen far more slowly than incomes and general prices. So, as real vehicle prices fell, the LCT’s narrow indexation pulled more ‘ordinary’ cars into the luxury tax bracket:

In optimal tax theory, the goal is to raise a desired amount of revenue while minimising the distortions in consumer behaviour or productive economic activity per dollar raised. The worst sort of taxes tend to be narrow and goods-specific—like the LCT. They’re even worse when they rely on an arbitrary threshold, which incentivises manufacturers to manipulate vehicle specifications or trim features to fit just below that level, generating a deadweight loss disproportionate to the revenue raised.

Indeed, one reason why Trump’s tariffs are so bad is because they vary by country, and he frequently dishes out exemptions for specific goods. So, companies will waste resources rerouting trade through the lowest-cost countries, spend enormous sums on rent-seeking to secure exemptions for specific goods, and consumers are forced to adjust their purchasing patterns.

If Trump had just whacked a 10% tariff on all countries and all goods, the deadweight losses relative to revenue raised wouldn’t have been as bad. In fact, if they replaced more distortionary taxes, they could even form part of an optimal tax structure.

The same is true in Australia: yes, the government loves the ~$1.2 billion in revenue the LCT generates, and the ‘victims’ are largely at the top end of town, making it a politically resilient tax. But it’s still a bad tax, will get worse over time as more people are caught up in it, and if Treasurer Chalmers was actually serious about reform and improving Australia’s productivity, it should be one of the first taxes on his chopping block.