Australia’s fertility rate has been below the “replacement rate” (2.1 babies per woman) since the 1970s. Migration has filled the gap since then, but “migrants themselves age and tend to have slightly lower fertility rates than those born in Australia”.

An older, and eventually smaller, population creates fiscal problems (e.g. pensions and healthcare) for a country already struggling with structural deficits where government spending consistently outpaces nominal economic growth.

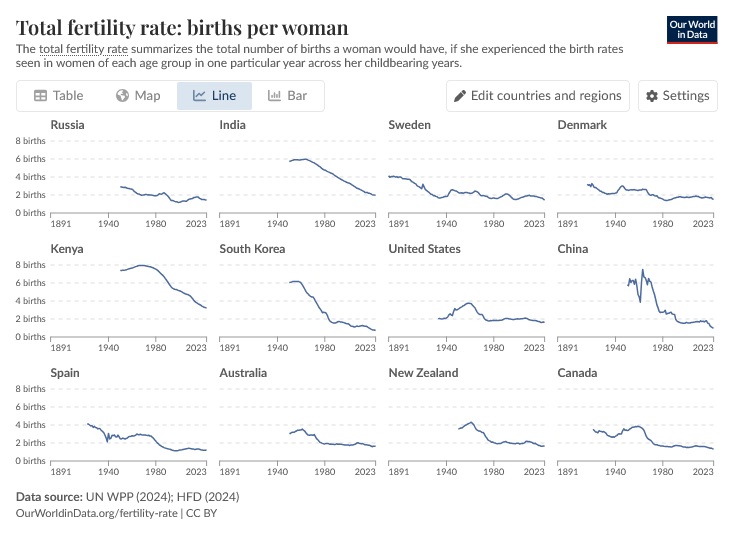

Declining fertility rates are not something unique to Australia:

I’m not aware of a country that has been able to arrest the decline; social norms have clearly changed against having large families and such norms can be incredibly durable. Still, the politician’s syllogism is real so where there’s a perceived problem, something must be done!

Enter former Prime Minister John Howard:

“Treasurer Jim Chalmers is being urged by former prime minister John Howard and the Coalition to bring back the baby bonus to defuse a ’ticking demographic time bomb’ of low fertility rates.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data for NSW shows fewer babies are being born, more people are leaving the state and only sky-high immigration rates are boosting the population.

Demographers and politicians are now urging Mr Chalmers to reintroduce the $3,000 baby bonus brought in by treasurer Peter Costello in 2004 to increase the birth rate.

At the time he encouraged young Australians into the bedroom with the slogan: ‘Have one for mum, one for dad and one for the country.’”

Lots of countries have tried to throw cash at people to have babies. Perhaps the most extreme modern example is Hungary, where strong pro-natal policies arrested the decline in birth rates for several years, only for them to fall to an all-time low in 2024. Whether the trend reverses again remains to be seen.

But incentives matter, and giving $3,000 to every new parent will no doubt boost the birth rate. However, it’s debatable whether it will simply produce a temporary shift in timing (pulling forward births) or lead to a boost in total fertility. Evidence from around the OECD (Australia is by no means alone in giving cash for babies!) suggests such transfers produce extremely small long-run effects.

There’s also another big difference between today and when Howard and Costello splashed some of their temporary budget surplus on a similar social experiment: Australia is now in debt and the federal budget is in structural deficit.

Basically, a baby bonus today would be equivalent to borrowing from the future to pay for what may well be a temporary increase in babies. And those babies—who may have been born anyway, albeit a bit later—would then be the ones forced to pay back the debt.

I’m just not so sure that’s even close to being the best use for our country’s increasingly scarce fiscal resources. Indeed, a better use of those funds might be to address the supply-side constraints that make family formation so expensive in the first place, from liberating well-located land for housing to reforming childcare and simplifying costly zoning regulations.