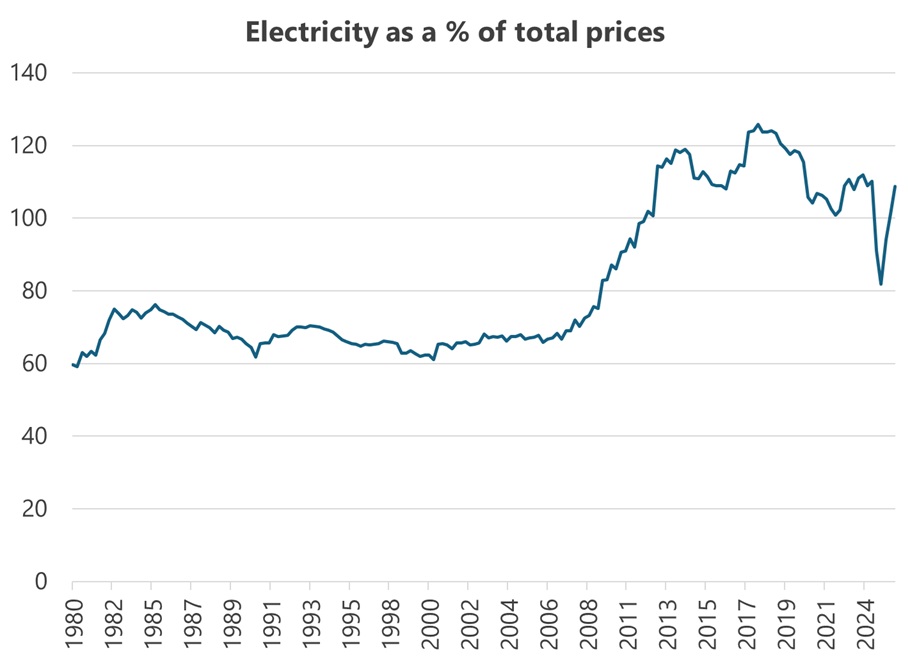

It’s no secret that Australia has been in something of an energy crisis for around a decade now. Retail energy prices have been rising faster than most other goods and services, and—perhaps more importantly—are now significantly (2x) higher than in peer countries such as Canada.

To mitigate the consequences of the crisis federal and state governments have been papering over the ever-widening cracks with a long list of policies to treat the symptoms, artificially suppressing prices. Household energy rebates, life-extending investments in ageing coal plants, revenue guarantees for renewables, retail price caps, wholesale price caps, household appliance subsidies, rooftop solar rebates, and home battery rebates—it’s all part of a plan to keep the lights on without affecting sticker prices too much.

But that tangled web of taxpayer-funded subsidies, mandates, and distortions can’t go on forever. At some point, Australia’s politicians will need to come to grips with economic reality: if you want to transition away from fossil fuels like coal in the name of climate change, there is no free lunch; someone is going to have to pay the price.

So how did we get here, and what can we do about it?

Climate policy shouldn’t drive energy policy#

Combating climate change and providing abundant, affordable energy to Australians are separate issues, and should be treated as such. Setting goals like renewable energy targets as part of climate policy risks impoverishing Australians for little, if any, benefit.

That’s because it’s becoming increasingly obvious that despite all the noble ‘pledges’ to reduce carbon emissions, the world is not even close to backing net zero with policy action. Yet Australia has legislated targets of reducing emissions to 62-70% below 2005 levels by 2035, and to go fully net-zero by 2050.

If we achieve those goals, we’re suckers. Those targets are far more aggressive than what the USA, China, or India have committed to on a comparable timeline. Why should Australian households and industry bear costs that our competitors aren’t?

Remember that climate change is a global issue; per capita emissions are irrelevant, and Australia accounts for just ~1.1% of global emissions. Even if we went to net zero tomorrow, it would be equivalent to a rounding error on the dial of climate change if the big three of the USA, China, and India don’t move—and they don’t look like budging any time soon. If doing so comes at a large cost in terms of energy prices and reliability degradation, then it’s almost certainly not worth doing.

Therefore, the optimal position for Australia is to be a follower. Do you think President Xi cares how much carbon Australia emits? President Trump? Prime Minister Modi? No amount of positive vibes or ‘setting an example’ will change the fact that Australia is tiny in a global context and has very little influence over the real players. So, on climate policy, the economically rational position for Australia should be something like:

We’ll decarbonise our energy sector if and when it’s economically sensible, but unilateral sacrifice is pointless.

On energy policy, we should be phasing out coal because it’s filthy and harmful to Australians and those costs aren’t captured in its price, not because it will help us achieve some arbitrary emissions target that will make zero difference to climate change.

Stop clamouring for coal#

It’s perfectly consistent to support renewables—which are economically competitive, up to a point (more on that below)—but reject the Albanese government’s 82% renewables target, which mandates a specific technology mix rather than focusing on reliable, affordable energy for Australians. It’s also perfectly consistent to reject calls for new coal plants, which is the same error but in the opposite direction:

Unlike renewables and gas, coal plants are capital-intensive and have to run all day and night to recover those costs. That means they can’t adapt to the intermittent nature of renewable generation, and can’t compete with the zero or negative daytime prices that renewables produce. In a system with high renewables penetration—which Australia has—building more coal power plants is prohibitively expensive even without counting the political risks, unlike gas turbines or batteries with synchronous compensators that mimic turbines to keep the grid stable.

In an ideal world, climate policy would consist of nothing more than a carbon price pegged not on some arbitrary net zero deadline built on empty promises, but at a level that matches some global benchmark of existing carbon-reduction policies. Any revenue generated by the tax could be used to offset more destructive taxes elsewhere. Trade-exposed sectors could be given some concessions, at least initially, to prevent any ‘carbon leakage’ where production might move to countries with weaker climate policies as a result of the tax. Australia’s energy system would adapt when and where it was economical to do so.

But that’s not the world we live in. The failure of the Gillard and Abbott governments in poisoning that idea in the minds of the electorate means we’re left with nth-best options for climate policy. But just because we’ve trashed our climate policy doesn’t mean we can’t still have sensible energy policy. Anyone who claims to have the answers as to what the right energy mix should be is making a political, rather than economic, point.

Renewables are the future but not at any cost#

Renewable energy generation is remarkably cheap. Mass production of solar courtesy of China, combined with generous subsidies, has driven down costs to the point where you should almost have rooftop solar PV on every building in Australia (and we do!).

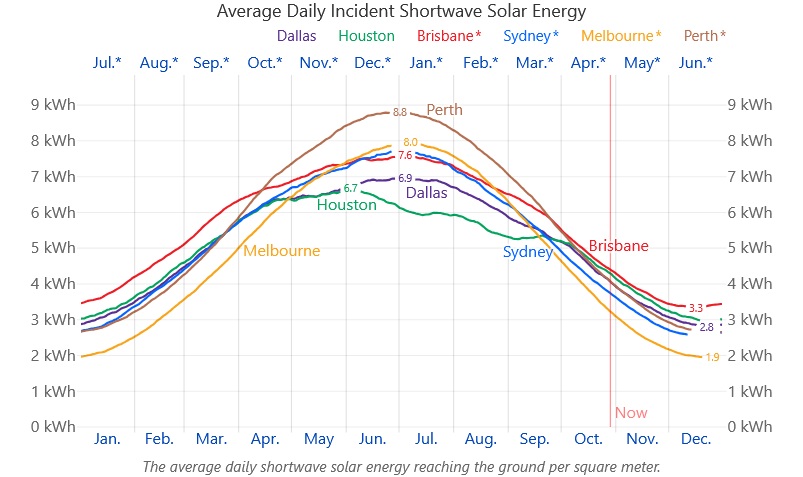

Indeed, almost every major Australian city—sorry Hobart, but hey, you have ample hydro—receives at least as much solar exposure as Dallas and Houston (although Melbourne does drop off a bit in winter).

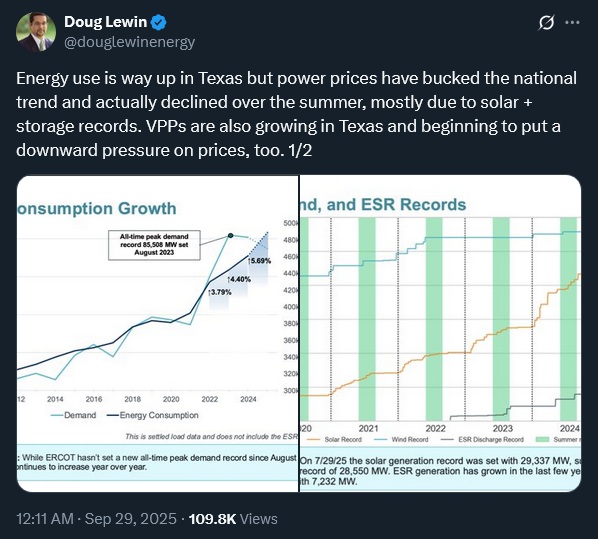

I’m comparing Australian cities to Dallas and Houston because Texas is showing how competitive solar can be in what’s a relatively free market for energy:

“Texas has its own electricity grid, run by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, and a market that requires owners of power plants to compete on price. This is different from most of the country, where power plants have guaranteed profits under state regulation.

Texas also is friendly to developers in terms of obtaining permits to build projects and connect to the grid. This, too, is different from most of the country, where developers often need to work through years of obstacles from local governments, state regulators and regional grid operators.

“Texas is the most innovative, most interesting market, and clean energy is thriving because it makes sense economically,” O’Connell said.”

I’m less convinced by wind—especially offshore—in Australia, given NIMBY hurdles and their comparatively poor economics. Project after project is going belly-up, despite generous government subsidies.

But renewables alone are only one part of the energy policy puzzle. Unless you can properly store the energy they generate at inconvenient times, and transmit it in a cost-effective way, you run into a series of potentially catastrophic problems, from high costs to blackouts.

One of those ‘firming’ methods is by using gas. Unlike coal, gas turbines can be adjusted to meet demand. Worryingly, Australia’s leading climate policy bureaucrat, Climate Change Authority chairman Matt Kean, doesn’t appear to understand that Australia’s supply of gas isn’t just some bottomless pot he can dip into whenever he pleases, but requires long-term investment:

“The idea that there’s a gas shortage in Australia is laughable. There is a domestic gas shortage because the majority of the gas is being exported offshore, and 25 per cent of that gas … is uncontracted. So it’s not as if asking the LNG producers to provide that for domestic purposes is going to create a sovereign risk issue … We don’t need new gas supply domestically. We need existing gas supply, hypothecated for Australians domestically. That’s the challenge.”

By “asking”, Kean means “forcing”. And yes, it does create a sovereign risk issue: these are long-lived projects committed during times of considerable uncertainty, and many of those exports were contracted ex ante to provide the projects the certainty they needed to get up.

Contrary to Kean, it doesn’t take much political uncertainty to wipe out the potential returns investors hoped to earn, destroying projects before they ever see the light of day. Australia has had great success in the resources sector largely because we’ve been perceived as a safe destination for capital—i.e., that our governments won’t “ask” for a bigger cut after the investment has been committed. Kean’s comments don’t just damage the prospect of future gas investment in Australia, but all investment.

The solution isn’t forcing existing projects to redirect exports, but removing barriers to new supply. That means streamlining approvals, reducing ‘lawfare’ that can hold up projects for years, and providing regulatory certainty so investors will commit capital. Australia has abundant gas reserves; the constraint is political, not geological.

But back to prices: in the same article linked above, UNSW economics professor Richard Holden calculated that gas prices and electricity prices are almost perfectly correlated at 0.945. As I’ve written before, that’s because:

“Network prices are determined by the marginal unit – i.e. the most expensive generator needed to meet demand – not the average unit, and right now that’s the gas burnt during peak periods.

…

To reduce electricity prices, Australia needs to lower the cost of the marginal unit. That can be done with cheaper gas, or better ways to store any off-peak renewables surplus, such as with a huge stock of batteries, hydrogen, or pumped hydro.”

Gas is essential in a renewables-heavy grid, and our governments should be seeking to unlock as much supply as possible. Not just for Australia’s benefit, but so the world can more easily decarbonise—isn’t Kean supposed to be chair of the Climate Change Authority?

Batteries are amazing; not-so battery subsidies#

Renewables, because of their intermittent nature, need storage to move the energy they generate through time. Gas is a good stop-gap, but batteries are the real key to the puzzle. As it turns out, Texas is also leading the US on that front:

“What has changed since last summer, when ERCOT was warning that grid shortages could occur? Developers built 5,395MW of solar capacity, 3,821MW of dispatchable battery storage and 253MW of new wind projects.

The reliability provided by these new renewable and battery storage resources stands in sharp contrast to the unexpected reliability problems that have hit ERCOT’s coal plants so far this summer. On July 11-12, 5,019 MW of coal-fired generation was offline across ERCOT—totaling 36.9% of the system’s accredited coal capacity of 13,596 MW. The reasons for the outages vary, but almost two-thirds of the total capacity offline was due to unexpected, short-term maintenance issues that ERCOT would not have planned for, forcing the system operator to turn to other resources for needed power supplies.

…

Meanwhile, renewables and dispatchable battery storage continue to demonstrate their dependability in the ERCOT system. New peak records were set earlier this month for both solar generation, which hit 28,071 MW on July 10, and battery storage, which discharged 6,309 MW into the ERCOT system on the evening of July 11, accounting for 9.2% of system demand at that point and reducing the need for that amount of coal or gas-fired generation.”

Developers are building batteries in Texas because their energy system rewards them for doing so:

“Independent developers, retail energy providers, and virtual power plant aggregators (diverse agents) respond to real-time prices and financing terms (local information) in accordance with their own preferences (private information), and their actions—charging and discharging batteries—influence future price signals (feedback loops). Every act of arbitrage flattens price volatility, reshaping tomorrow’s market conditions and incentives.

…

A midsummer day in 2024 tells the story. At 1 p.m., solar output and strong wind drove wholesale prices down to $15/MWh. Batteries began charging en masse. By 7 p.m., as solar faded and residential demand peaked, real‑time prices attempted to breach $500/MWh. Roughly 4 GW of batteries responded, discharging into the tight market and clipping the spike at around $250/MWh. Consumers saved tens of millions; battery owners locked in a healthy margin.That single afternoon dramatised the feedback at work. The next day’s price spreads shrank. Each successful arbitrage event teaches the market a lesson: evening scarcity is less severe than the previous day implied.”

Importantly, Texas’ government didn’t subsidise batteries. Subsidies are risky in the sense that it’s easy to over- or under-cook them, which risks creating a solar death spiral:

“In the short-run, it [battery subsidies] will ease the pressure on the grid during ’normal’ times as the few people with batteries use the grid as a backup instead of disconnecting entirely. Those semi-defectors are able to free ride on the rest of the state, using their own generation most of the time and only pulling from the grid when needed, at prices below what it costs to service their infrequent use.

In the longer-run, it risks bringing forward grid defection. A 2024 paper published in Solar Energy found that defection was a serious risk in ‘solar-rich locations that have high electric rates’, but governments should not try to ‘discourage on-grid PV systems’ – e.g. with higher fixed fees, or the WA government’s current policy of forcibly switching people’s solar off – as that will only ‘unintentionally incentivise grid defection’.”

Keeping people on the grid is critically important for its reliability and affordability, as the main costs of the energy system are not generation but transmission. The spiral can happen because grid costs are mostly fixed; as more households go off-grid, those fixed costs get spread over fewer users. Basically, if you incentivise people to generate their own energy and store it, but don’t use prices to incentivise them to also arbitrage, then you risk destabilising the entire system.

Given Australia’s large amount of solar and new battery subsidy scheme, there’s a reasonable chance that whole system costs rise as the battery uptake increases—at least under the current market structure, anyway.

Transmission, transmission, transmission#

The UK—which is ahead of Australia in terms of its renewables penetration—is battling world-leading energy bills not because of rising wholesale (generation) prices, but because of so-called ‘policy costs’ (i.e., subsidies for renewables).

Renewables might be cheap at generating power, but you still need to build the transmission networks to get that generation to where it’s needed—an added cost that needs to be recovered. If you gold-plate that investment, as Australia did in the 2010s and caused a big jump in relative prices shown in the very first chart of this post, energy prices will rise a lot.

The UK is finding that out, good and hard. Like Australia, it’s also an island that’s not connected to a broader network (e.g. Denmark), nor does it have much hydro (e.g. New Zealand). And the reason policy costs are rising so much in the UK is because of the considerable amount of transmission infrastructure that is being built to connect large-scale renewables to the grid. That’s going to make energy more expensive in the short- and medium- run, i.e. until those costs are fully amortised.

Here’s Oxford economics professor Dieter Helm:

“[The price of electricity] is going up, with a system requiring twice the generating capacity and much more transmission, lots of batteries and storage, and a great deal of back-up generation to keep the lights on, all to achieve the same amount of electricity. To think otherwise is to commit the broken windows fallacy – that by breaking windows, economic growth is increased. Replacing one set of windows with another is a net cost, and replacing the windows with more glass than was previously needed is a bigger cost still.”

We won’t be able to avoid similar costs in Australia if we continue to pull forward the supply of renewables with subsidies and grants. Indeed, I suspect that the modelling done to date has been far too sanguine about these costs; for example, a project led by the NSW government’s transmission company, Transgrid, “is running late… [and] costs were originally expected to be $1.8 billion, [but] they are now on track to be double that figure at $3.6 billion”.

If every project is run like that—or worse, like Snowy Hydro 2.0—then the renewables build-out will result in energy prices only moving in one direction: up.

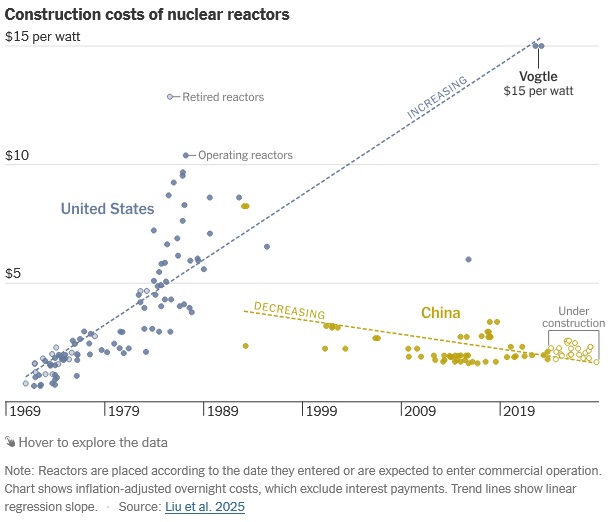

It’s time to legalise nuclear power#

There is no good reason, other than political inertia, for nuclear power to be illegal in Australia: it’s one of the safest and cleanest technologies available. But that’s not an argument for large-scale reactors to be built tomorrow; indeed, when Peter Dutton proposed doing just that prior to the last election, I wrote that “the viability of such large, vertically integrated energy utilities has been fading because of competition from solar and battery storage”.

All I’m asking is that nuclear power be legalised so that it’s an option for aspiring energy entrepreneurs at some point in the future. I don’t know what form that might take, if any, but if markets are open and contestable then anything’s possible. If your goal is for a low-carbon, safe, and affordable mix of energy generation, then you really shouldn’t be ruling anything out!

On that point, a key reason nuclear is less competitive than it should be is because for many decades, energy policy in western nations has deliberately increased the costs of nuclear. That’s actually an advantage for Australia—rather than copy the UK or US, we could import Korean or Chinese regulatory frameworks and ensure that any nuclear startups would at least be playing on a level field.

If Australia wants to boost productivity and make energy more affordable while maintaining its economic capacity to combat problems like climate change, governments must lay the foundations for innovation. Philippe Aghion—one of the recent winners of the economics Nobel Prize—has argued that the best way to fight climate change isn’t through some kind of forced energy transition, but with energy innovation. When the government has banned one possible avenue for such innovation to take place, it’s doing the country—and the planet—an unnecessary disservice. And unlike cigarettes, it’s not likely that a black market for nuclear energy is going to emerge anytime soon, no matter how high energy prices rise (in technical terms it’s a highly ‘specific’ asset, making it easy to confiscate).

So, any sensible energy policy in Australia should involve legalising nuclear energy and providing entrepreneurs with a clear regulatory framework that lets them build, if nuclear energy turns out to be commercially viable in Australia.

Above all else, embrace markets#

Energy feeds into everything, so it’s an important issue to get right. As demonstrated by Joel Mokyr, another recent Nobel Prize recipient, “energy innovations, or the ability to convert natural forces into mechanical work more efficiently and flexibly, have driven every major surge in productivity and prosperity”.

To promote a culture that fosters such innovation requires letting markets work. That means moving Australia’s energy policy closer towards something that resembles Texas, rather than the UK:

“The most critical factor in Texas’ rise to clean energy dominance is its open energy market. In most states, decisions about what type of electric generation to build require government approval or are made by monopoly utilities as part of a centralised planning process. By contrast, Texas leaves it up to investors to determine what types of energy generation to build. In recent years, companies have opted to build a lot of wind in Texas and now are investing heavily in solar and battery storage resources in the state. Texas also has the best regulatory environment for energy permitting of any state. While other states require wind and solar projects to go through some form of laborious state or local permitting process, energy developers in Texas who can reach agreements with landowners can build and connect to the grid easily.”

There will be no quick fix for Australia. We probably have 5-10 years before our ageing coal plants are retired, which will need a massive investment in replacement capacity. That’s going to come at a cost.

But what we don’t have to do is throw good money after bad. Stop conflating climate policy with energy policy. Get the energy market design right, set prices and their ability to coordinate free, and let investors and consumers determine what the right mix of generation should be. The real risk for Australia is that by pigheadedly pursuing an arbitrary 82% renewables target—a number that assumes the government can predict the optimal technology mix decades in advance—we lock in the current mess of subsidies, mandates, and distortions, and we’ll be stuck with it for the 30+ year lifetime of new assets.

There’s no magic wand that will fix this mess overnight. But we can make incremental progress: free up the constraints to investment, reward flexibility, shift time-of-use pricing from opt-in to opt-out, and most importantly, fix the regulatory barriers that prevent demand and supply from responding to price signals.