Today marks the start of Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ two-day roundtable on how to get Australia’s productivity growth moving again. I’m not at all optimistic that a gathering of the country’s elites will produce anything remotely close to a ‘fix’, but at least it’s being discussed, right?

On that note, the SMH’s long-serving economics editor, Ross Gittins, wrote about Australia’s lack of productivity yesterday. In standard Gittins form, he spent 90% of the column railing against businesses and economists, then accused the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) of “saying I’m responsible for inflation; productivity is someone else’s worry”.

Well, yes. Last time I checked, the RBA board doesn’t have an explicit productivity mandate; it’s tasked with setting monetary policy “in a manner that it believes best contributes to both price stability and the maintenance of full employment in Australia”.

But back to productivity. Gittins wants policymakers to abandon the “pro-business bias… [that] comes from the neoclassical model of the economy every economist carries in their head”, which has led to “unconstrained” growth in profits. In Gittins’ model, that’s a big problem because “the economy is circular: when business fattens its profits at the expense of its workers, those workers turn into households that don’t have as much to spend on the things businesses are selling”.

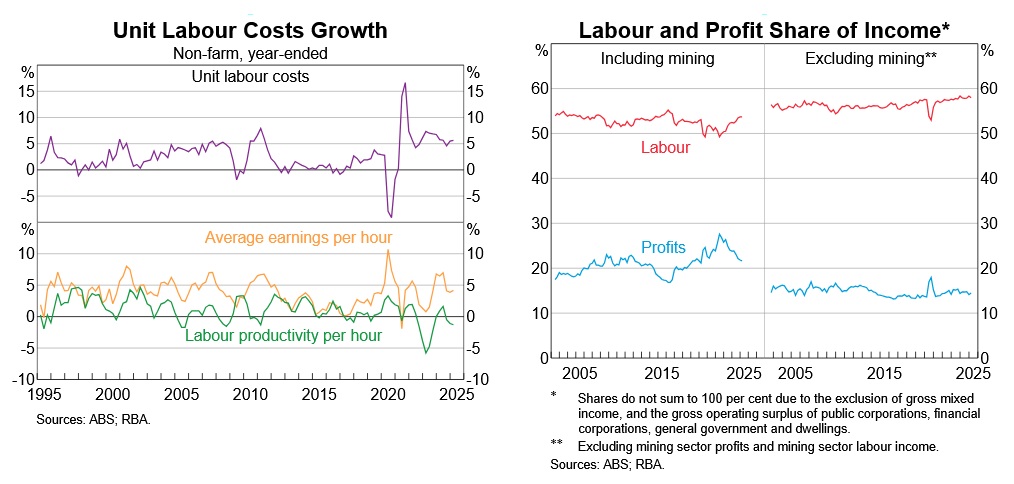

There are a few issues here. The first is the data: Gittins might spin a nice narrative about workers being ripped off by businesses and their economist handmaidens at the RBA, but the facts are that Australia’s labour share of income has remained remarkably stable over several decades.

Moreover, unit labour costs, which track what businesses pay workers to achieve a unit of output, have grown above 5% annually since the pandemic as earnings have outpaced productivity.

None of that is consistent with Gittins’ bold assertion that Australian policymakers have been willing to “tolerate businesses fattening their profits by finding ways to keep their wage bill down”. So, it shouldn’t be surprising that his grand policy recommendation is for someone (presumably government?) to raise productivity by raising wages:

“Back on productivity. One big reason businesses haven’t been investing much in the labour-saving technology that increases their productivity is that they’re not paying a lot for their labour. Use generous pay rises to raise the cost of labour relative to capital, then watch our productivity improve, retrospectively justifying the generous pay rises.”

If only the real economy worked the way Gittins’ model of the economy does. We could just crank up the minimum wage to $50/hour (nearly half the workforce’s pay is linked to this rate), households would start spending the windfall, profits would soar, and we’d all become gloriously wealthy!

Unfortunately, Gittins has the causality reversed: it’s productivity growth, driven by capital deepening and technological innovation, that raises the marginal productivity of labour, which then translates to higher sustainable wages. To fix productivity, policymakers should fix the structural problems (e.g. the tax mix) that make Australia a more costly and less competitive place for capital investment.

What would happen if Gittins got his way is unemployment would skyrocket (as labour costs would exceed marginal productivity), inflation would surge because the RBA would look to use monetary policy to soften real wage growth and unemployment, businesses would fail, and investors would actively avoid sinking capital in the economic backwater that Australia would become.

That’s the world according to Ross Gittins. I only hope that those attending Chalmers’ roundtable are smart enough to know what not to do!