At the end of September my brother and I spent a weekend in Tokyo, Japan. It was by no means our first trip; we lived there for about five years as kids, and I’ve personally been back dozens of times since. In fact, I’m jetting off again in a few weeks for an extended stint in the land of the rising sun (the literal translation of Nippon, or Japan), before heading to Canada for the Christmas break.

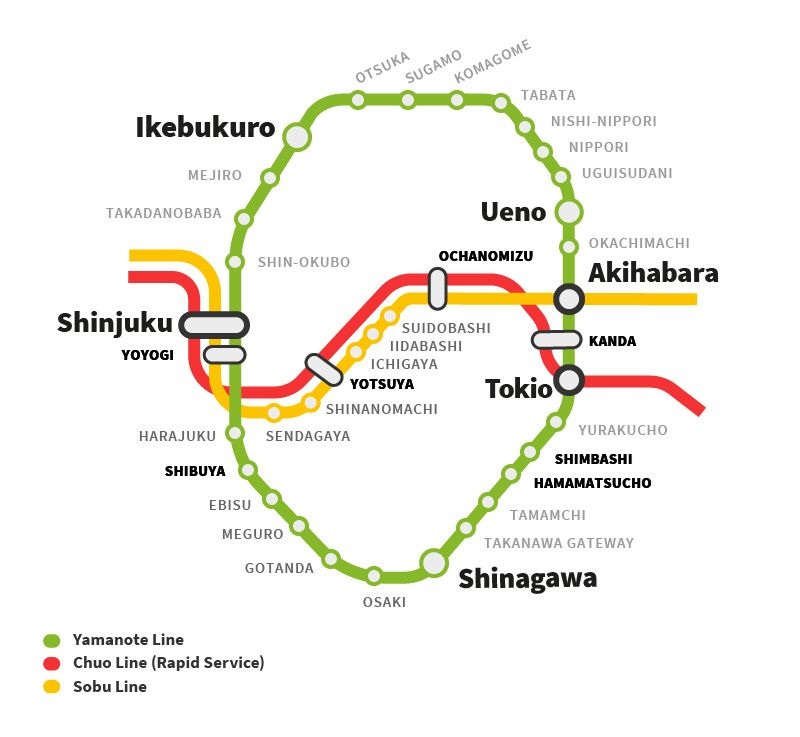

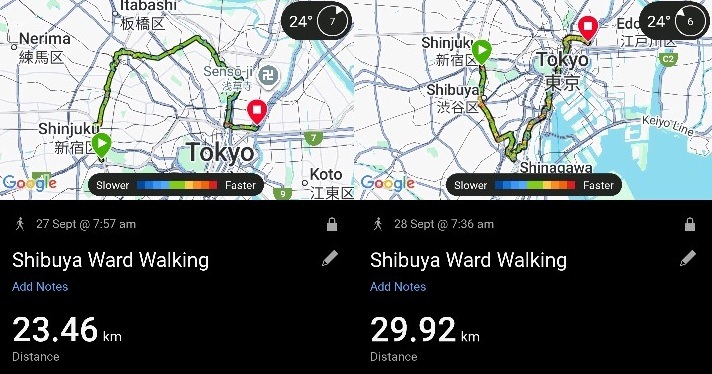

But what made this particular trip different was the purpose: we’ve been going on annual hikes for a long time—trails like the Cape to Cape, or mountains such as Rinjani—but we had never hiked a city. So we set out to walk the Yamanote (green) train loop, which roughly marks the boundary between Tokyo’s urban core and its outer suburbs.

The entire line is more than a marathon, so we split the walk in half. Starting at Yoyogi (home of a beautiful park), on the first day we would tackle the north side, and on the second day the south.

We broke it up that way because we also wanted to attend the sumo in the afternoon, and the stadium just happens to be closest to Akihabara station—which we ensured was our final stop on both days by catching the express Sobu line to Yoyogi each morning.

Given the distances and time constraints involved, we didn’t have all that much time to take in the urban environment. Still, I left with a few key take-aways.

Possibly the most walkable city in the world#

No matter where you go in Tokyo, you’ll inevitably find yourself within a short walk of a konbini, or 24/7 convenience store. Unlike the equivalent in Australia, these stores will have just about everything you need—fresh food, cold drinks, socks, medicines, cash (foreign cards at 7-11 only). You name it, they’ve probably got it. Pair that with the well-stocked vending machines on every street, and you don’t need to worry about carrying anything other than a phone and wallet.

Another reason why Tokyo is so walkable is there’s virtually no visible crime. Japan scores better than the notoriously anti-crime Singapore on the global crime index, thanks largely to culture and strong enforcement. While I’m not suggesting you actively seek them out, even ‘bad’ neighbourhoods in Japan feel relatively safe compared to what might be considered an average neighbourhood in an Australian city.

That said, one morning we did pass a group of youths still kicking on from what sounded like a big night, with a couple choosing to relieve themselves on the side of the road. Yes, kids will be kids—even in Japan!

Another reason Tokyo is so walkable is there are so few cars outside of the major arteries. The residential roads are extremely narrow and have no footpaths to speak of, and houses are not set back much at all. I suspect that’s because their narrow, windy nature deters motorists from using them, and effectively forces any local residents to drive not much faster than pedestrians can walk. We did a lot of road walking as a result and it often felt safer than walking on dedicated Australian footpaths.

The ample public bike storage near train stations and limited car interactions also meant we saw plenty of cyclists, none of whom were wearing helmets, other than the odd child.

There’s almost no wasted space#

The Yamanote line itself forms something of a hub; rather than wasted space, people congregate in the areas between stations. Businesses set up shops directly underneath the line, which is elevated most of the way.

What about a rail crossing, under which you might expect to find a few people sleeping rough in a major city in Australia, Canada, the UK, or US? In Tokyo the space was almost always put to commercial use, with a couple of stores fronting the street but many more inside what’s know as a yokocho, or alleyway filled with small bars, eateries, and izakayas.

Needless to say, finding a place to stop for a meal was never an issue!

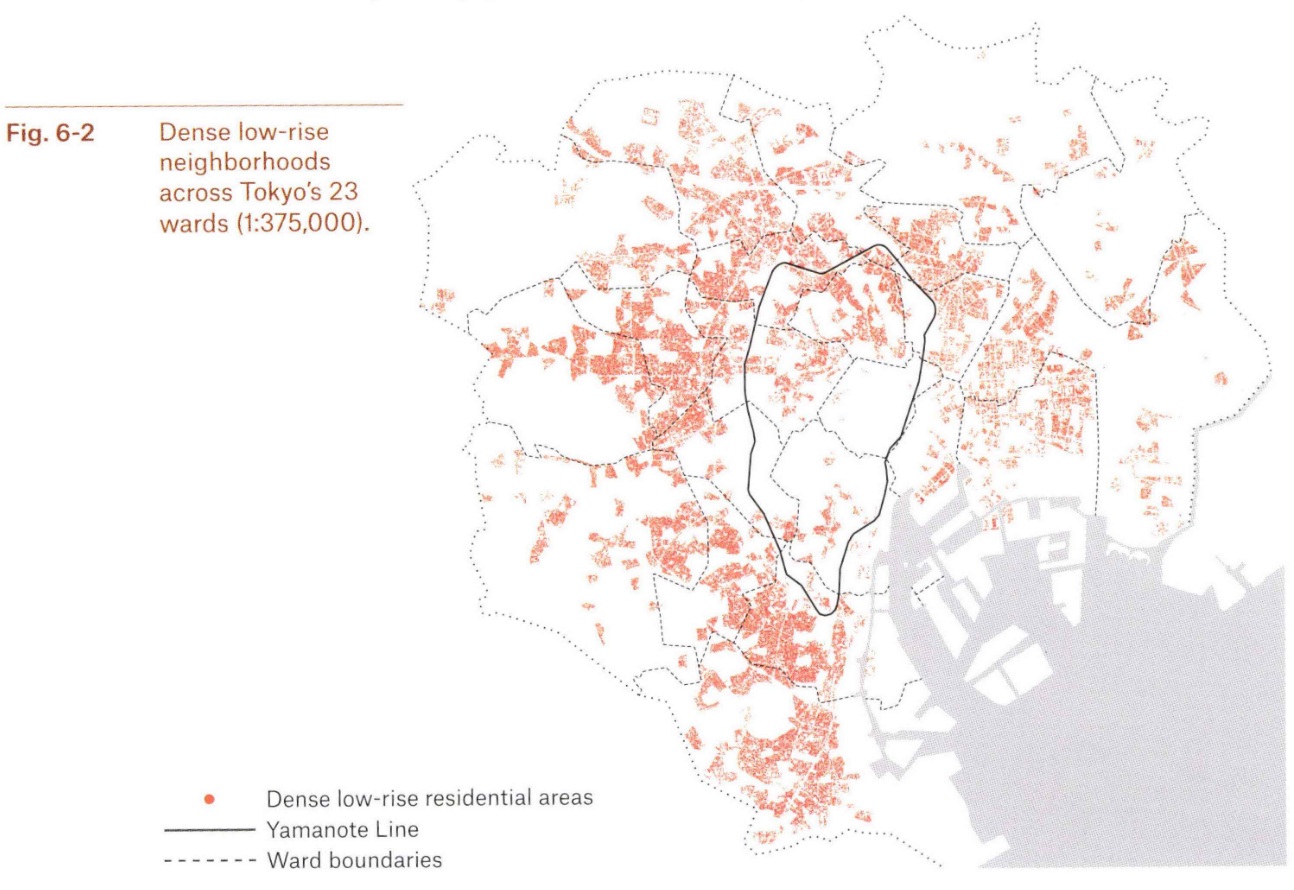

Density doesn’t have to be tall#

Tokyo is famously dense. While cities like Melbourne are denser at their core, in Tokyo the density doesn’t drop off; there is no missing middle. You have skyscrapers flowing into two- or three-floor townhouses interspersed with detached dwellings and even sprawling, security-guarded mansions.

The reason for that is Tokyo largely unplanned, at least as we’d refer to the concept of urban planning in Australia. A recent book called Emergent Tokyo by Joe McReynolds and Jorge Almazán looked at how Tokyo essentially emerged from the bottom up, rather than the heavy hand of the state prescriptively dictating what people can build from the top down.

Basically, zoning is extremely permissive, licencing requirements are virtually non-existent—you can buy a beer anywhere, even from a vending machine—and there are no minimum block sizes, setback requirements, or parking mandates.

“Narrow streets and small single-family houses are common in Tokyo neighborhoods, at times resulting in an atmosphere more reminiscent of a quiet village than a bustling metropolis. And in the areas of Tokyo that are relatively dense, that density is achieved through a tightly knit, fine-grained, low-rise urban fabric of houses with high plot coverage. What this means in a practical sense is that the layout of these neighborhoods resembles a frantic Tetris game rather than a neat and spacious suburban grid, earning them comparisons in some respects to the so-called slums of the developing world. But what looks at first glance like disorder is in fact the natural result of organic, bottom-up growth—the same quality that makes these neighborhoods so livable.”

The result is a city where people are free to innovate. A tiny triangle of land adjacent to a pedestrian staircase? What a great place for a small stand-up only bar!

Tokyo is a dense city but most people still live in relatively low-rise houses, rather than the high-rise ‘dog boxes’ that NIMBYs claim would be the inevitable result of zoning relaxations in Australia.

It wouldn’t take much to double or triple the density in most Australian cities while still maintaining low-rise living for those who want it, as is the case in Tokyo. The reason we seem to have nothing but apartments or detached dwellings has more to do with rules making everything in between impossible to build—whether explicitly banned or implicitly blocked with rules, charges and processes that make them unviable—than consumer preferences.

The public transport is excellent#

You can’t visit Japan and not be impressed with the public transport, whether it’s the frequent, reliable trains, or the buses operating high frequencies on more direct A->B routes, such as between the two major airports.

In Australia, rail lines are government owned and operated and lose a significant amount of money each year because that’s all they tend to be: rail. There’s not much activity at all around the stations, let alone along the lines themselves. Rather than implement user charging for roads or permit density via bottom up zoning rules to improve the relative profitability of rail, governments deal with sprawl by building lines out to distant suburbs that run empty most of the day.

Take the following example. Hong Kong’s (profitable) MTR network has 98 heavy rail stations for a population of 7.5 million. Perth’s METRONET (not an acronym) has 78 heavy rail stations, with another 8 planned, for a population of just over 2 million. METRONET loses around $2 billion a year.

Rail in Tokyo used to be dysfunctional too, until the government was forced to split up and privatise its loss-making monopoly network. Under private ownership they were then incentivised to diversify to remain financially self-sufficient, monetising their underutilised real estate holdings at stations and expanding to where the people were:

“These neighborhoods are not isolated, car-dependent suburbs. The population of these areas can easily access central Tokyo via convenient suburban railway connections. The suburban tranquility of dense low-rise areas comes coupled with commutes under an hour to the urban core’s hubs of activity and opportunity. Commercial centers around each station offer services ranging from hospitals and clinics to schools and shotengai commercial promenades, allowing locals to smoothly handle their needs along their daily commute. This arrangement is usually the result of intentional planning by suburban railway operators, who hold substantial real estate interests in the communities their lines serve.”

Basically, you can’t put the cart before the horse. There is no ‘build it and they will come’; you need density to support rail, rather than the other way around. If Australian governments want walkable, connected cities, then they first need to plug the gaping hole that is housing’s missing middle.

Tokyo is very affordable#

When we visited the Australian dollar was approximately equal to 100 Japanese yen. That, combined with the lack of nominal price inflation in Japan over the last few decades, made for a very affordable trip:

- We flew Scoot via Singapore and Taipei for something like $700 (thankfully the return flight didn’t involve a double stop!).

- A beer in a restaurant set us back about $6.

- A cheap meal—think a Yoshinoya beef bowl set—was around $5.

- Our capsule hotel, in a great location across the river from the sumo, was around $45 a night.

So, if you’re looking for an affordable, comfortable, and almost certainly enjoyable trip, I would highly recommend walking around a Japanese city. And definitely get to the sumo, although beware that tickets sell out incredibly quickly (within minutes) on the official website. Your best bet is to target the mid-week sessions earlier in the tournament.

Finally, be warned that if Japan feels affordable for Australians with the Aussie dollar at 65 US cents, it’s going to feel downright cheap for Europeans and Americans, of which there are now plenty running around all the main attractions on the so-called ‘Golden Route’ from Tokyo to Hiroshima. Let’s just say that many of these more recent tourists aren’t exactly the most… culturally sensitive, and so you might find Japanese hospitality in those places to be a bit less welcoming than it is in most of the country.