I’m a big fan of a four-day work week, and was even fortunate enough to work on such a basis during my last role at Treasury. But I’m no miracle worker, and I took a 20% pay cut to do it—there’s just no way my productivity at Treasury increased by enough to offset the missing day.

Now Australia’s largest union, the ACTU, plans to pressure Treasurer Jim Chalmers into passing a law mandating a four-day workweek for everyone—but with no change to take-home pay:

“Australians would benefit from a shorter working week – including a four-day model – under a proposal that unions will take to next week’s Economic Reform Roundtable.

The ACTU will argue that workers deserve to benefit from productivity gains and technological advances, and that reducing working hours is key to lifting living standards.

Unions will propose that Australia move towards a four-day work week where appropriate, and use sector-specific alternatives where it is not. Pay and conditions, including penalty rates, overtime and minimum staffing levels, would be protected to ensure a reduced work week doesn’t result in a loss of pay.”

In defence of its position, the ACTU cites two studies showing that a shorter week “boosts performance, reduces burnout and improves employee health and retention”.

Nature published the first study and it did indeed confirm those claims. But it said nothing about productivity, and it’s not exactly a revelation that working fewer hours for the same pay boosts workers’ self-reported well-being. Moreover, the paper suffers from a common fatal flaw found in many such studies: selection bias. The researchers didn’t select the firms at random; they volunteered to make the change!

The second study was a survey of ten real-world Australian companies that trialled “the 100:80:100 model, in which employees keep 100% of what they were paid for five days while working 80% of their former hours – so long as they maintain 100% productivity”.

All ten reported the same or greater productivity, despite the reduction in hours, and four of them made the change permanent after their trials.

While that’s all well and good for those firms, there’s still a lot of information missing before forcibly rolling it out to the entire country. For example, on top of selection bias, perhaps those firms paid less than their competitors, and management used flexible working arrangements to raise total compensation without touching wages? Perhaps the Hawthorne effect, where “individuals modify an aspect of their behaviour in response to their awareness of being observed”, played a role during the trials?

The author of the survey rightly cautioned that reporting on such trials elsewhere in the world has often “exaggerated the findings or failed to consider the complicating factors that may not make the model scalable”.

But while the ACTU might be forgiven for engaging in a bit of confirmation bias, there was no excusing what followed:

“Unions argue that Australia’s slow productivity growth is the result of a lack of investment by businesses in capital, research and people.

Analysis by Dr Jim Stanford from the Centre for Future Work in his recent paper ‘Productivity in the Real World’ also shows the scale of the gap between productivity growth and wage growth. If real wages had grown at the same rate as productivity since 2000, average wages would be around 18 per cent higher – or about $350 per week – than they are today.”

As someone who has spent a lot of time looking at productivity and real wages, that second paragraph immediately set off all sorts of alarm bells. After all, Australian productivity and real wages correlate very well in the long run!

So, I decided to dig up the research myself (the ACTU don’t provide links to anything) and take a look at how Stanford could possibly have produced those figures. And it was grim reading.

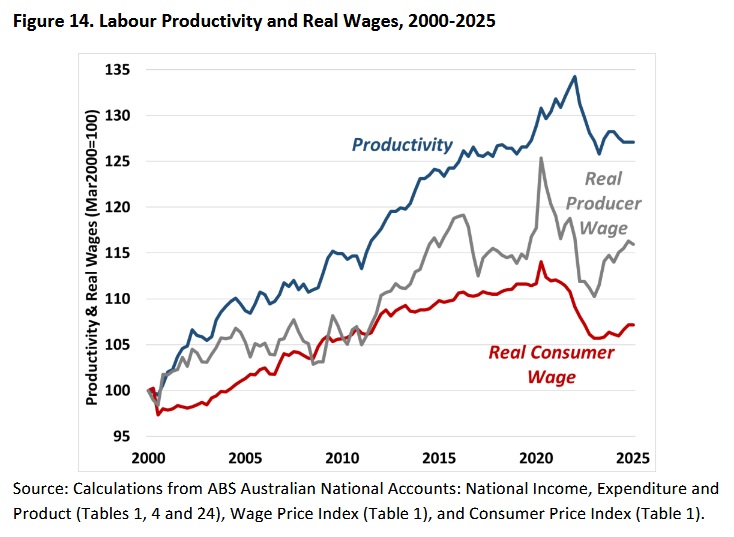

After demolishing several strawmen, including “what is predicted by ’trickle-down’ theory”, while providing no evidence that said theory even exists (the footnote leads to a paper examining the use of labour productivity as a measure for regional development initiatives), Stanford makes the above claim on page 56. He supports it with the following chart:

Immediately that looks suspicious: how is there such a huge gap between real consumer wages and productivity? If Australia’s labour market was even remotely competitive, some of the implied rents currently being enjoyed by employers would surely have been bid away. Are Australian companies seriously letting other firms pay workers an average of 18% less than what they contribute to a company’s output, and not offering them a slightly higher wage to lure them away?

Add in the fact that the labour share of income—especially after you strip out the distortionary mining and agricultural sectors that swing with global commodity prices, which Stanford does not do—is largely flat over many decades, and the finding simply doesn’t hold up.

So, how did Stanford get there? It turns out the devil is in the assumptions:

“Another common measure of wages is the Wage Price Index (WPI). It measures changes in wage costs across a fixed basket of jobs (analogous to how the Consumer Price Index measures changes in prices for a fixed basket of consumer goods and services). The WPI does not reflect changes in the composition of work (across industries, or between different types of job), and hence is a more focused measure of true wage inflation. For workers, the real purchasing power of wages depends on the prices of consumer goods and services which they buy. So, from their perspective, real wages could be estimated by deflating the WPI by the CPI. This is called the ‘consumer wage’.”

There are two main errors that lead Stanford to his erroneous conclusion. First, the WPI tracks employer labour costs for specific jobs, not workers—a flaw he partially acknowledges (“does not reflect changes in the composition of work”) but then immediately misapplies. There are other issues with the WPI too, including that it can be a poor proxy for total compensation because it misses non-wage benefits, bonuses, and the before-mentioned compositional changes that affect worker welfare.

Second, using the CPI to deflate the WPI is problematic because the CPI’s fixed basket ignores actual household spending shifts (substitution/composition effects), something that is especially important during periods of rapid adjustment (like a pandemic!).

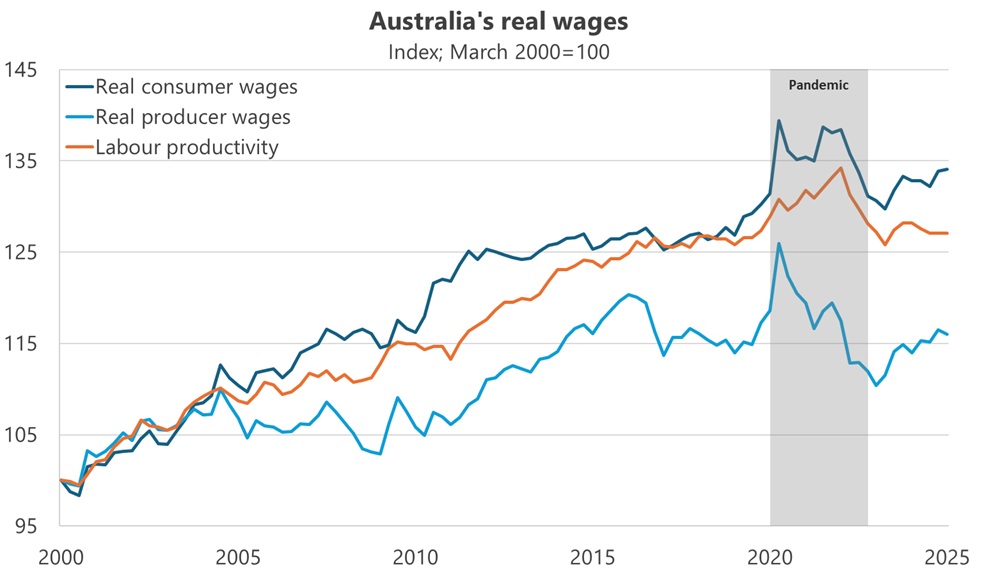

I don’t want to ascribe malice here, but what makes these errors especially odd is Stanford didn’t need to perform any of those statistical gymnastics. Economists typically define real consumer wages by deflating total non-farm compensation per hour worked by household final consumption expenditure (e.g. see the IMF, Treasury). That method aligns the compensation measure (total labour cost) with the consumption basket (actual household spending).

Real consumer wages = (Compensation of employees per hour) / (HFCE implicit price deflator)

If we fix Stanford’s assumptions accordingly, the chart then looks something like this:

If there’s a gap between productivity growth and wage growth in Australia, it has usually flowed in favour of the latter. Any attempt to artificially raise wages by the supposed 18% gap quoted favourably by the ACTU, for example by shortening the workweek to four days (-20% hours worked) with no change in wages, would lead to economic disruption the likes Australia has never seen.