This is the first in a new series called JWalking—posts about the economics of cities, discovered by walking through them. I’m not going to tell you the 10 must-see sites in a city, or my 10 favourite restaurants. Instead, I’m interested in why cities look the way they do: what enables certain businesses to exist, why prices vary by location, and how regulations shape what you can build and where.

For now, all JWalking posts will be collected at aussienomics.com/jwalking. This first one is about Tokyo’s permissiveness—why almost anything goes, and what that creates.

---

I’m writing this post on a rainy day – walking in the wet is both unpleasant and less interesting because most people are sheltering indoors – from the lobby of a capsule hotel in Asakusa, Tokyo. If you’ve never been to Japan, capsule hotels are essentially hostels where you rent an enclosed pod for the night instead of a bunk bed. I’m not sure exactly why they don’t exist in Australia, but it probably has something to do with a combination of more stringent building and fire codes along with mostly-NIMBY councils that simply wouldn’t consider issuing permits for ‘commercial sleeping pods’ in the first place.

I mean, let’s be real: the single-elevator, 8-floor hotel with 144 beds where I stayed in Tokyo likely wouldn’t be granted planning approval in Australia.

Japan is different. In Tokyo alone there are hundreds of capsule hotels operating legally. It’s just one of many features of the city’s permissibility: in Tokyo, people are generally free to do what they want within a given set of broad, rather than prescriptive, rules.

For example, in Sydney getting development approval can be a highly uncertain process taking “anywhere from a few days to years, depending on the complexity of your project, the council’s workload, and how prepared you are”.

And even if land is zoned for a specific purpose – say, medium-density apartments – in practice “other controls such as minimum side and rear setbacks, and minimum private open space rules, [mean] it quickly becomes difficult to build”.

There are no such restrictions in Tokyo; just look at the (lack of) open space and setbacks on these mostly-residential streets that I encountered on my walk.

You can build just about anything in Tokyo (both up and underground) because the rules are “by right”, in that if you tick pre-existing boxes set by a central authority, local approval is all-but automatic. If you need to build, it takes a standard one to two months from the receipt of an application for a construction permit, a process that is such a non-issue that when architects summarise the process they don’t even include it in their timeline.

That’s perhaps one reason why Tokyo has grown so much. While Japan as a whole has shrunk in terms of population since its peak in 2010, and today it has fewer people than it did in 1987, Tokyo has moved in the opposite direction. It’s estimated that fourteen million people live in Tokyo proper, with another twenty million or so living in the greater Tokyo area. While back in Australia we have former Treasury Secretaries saying we should be building brand new cities because Sydney and Melbourne are ‘full’ at circa-five million people, Tokyo shows that there really aren’t limits to human ingenuity or a city’s capacity when they’re not excessively restricted.

People want to live near where the good jobs are, and Tokyo lets them do that.

---

Given its sheer size, Tokyo is not a city you can walk and observe in a day. In fact, you probably couldn’t even walk it in a lifetime; it changes so frequently that by the time you were done, you’d have to start all over again. So, when I set out to walk around parts of Tokyo, the first question I asked myself was: where do I even begin? I couldn’t come up with a better answer than from my capsule hotel, so on both days that’s exactly what I did (a third planned day was washed out).

On the first morning, I left the Asakusa capsule hotel and walked north through residential Taito, before heading West and looping back around. I’m not sure how long the whole walk was, but by the end of the day my watch reckoned I’d walked about 25,000 steps—so probably something like 20km. I did something similar on the second day, although in the opposite direction.

After passing a pachinko centre that had multiple queues of people waiting to get in to blow their hard-earned (I guess gambling is just human nature, rather than culture), it wasn’t long before I found myself walking down Tokyo’s quiet, mostly-residential streets.

Both people and vehicles were sparse, and the average age of those I did see was probably closer to 70 than Japan’s median age of around 50. At the time I wasn’t sure if it was because of the time of day (late Saturday morning), or if young people just don’t live in Tokyo’s urban core. But when I walked through them on Monday morning the demographics were similar and they were just as quiet, suggesting that big city and serenity can co-exist.

But while the side streets were quiet, the buildings were anything but. There’s almost no wasted space in Tokyo; other than the roads and footpaths, everything has a purpose. When there’s not a townhouse or apartment block occupying the space, there’s probably going to be a micro car park. Even blocks without a physical structure on them are quickly put to use, like for this storage business.

In Tokyo, you don’t need to spend years fighting local and state governments over zoning and licencing to open a business. You can just do it.

Quite literally: to open up a shop, all you need to do is file a simple tax opening notice within one month after starting whatever it is you’re doing (it’s a bit more for food and personal services, but we’re talking a week or two). It’s why there are small businesses everywhere; the more I walked, the more I would ask myself questions like “Does Tokyo really need this many hair salons?”, or “How does a bar with five stools even survive?”

There was just so much variety, even in places you wouldn’t expect there to be. A butcher on a residential street, with queues out the front? But of course, because… Tokyo! It’s not zoned commercial because there’s no such thing as a pure residential or commercial zone. It just exists because someone had an idea to open it and enough people want it to continue existing by shopping there.

There are clearly very few restrictions on what you can and can’t do to try and make or supplement a living, or how to choose to live. Hawk homemade goods or run a side business from your garage? Go for it. Open a fruit stand opposite a giant supermarket? Why not. Tiny food vans in front of an British pub? I suspect the permit, if one even exists, was probably a single-page form along with a small administration fee—as much as the British pub might wish otherwise.

A smoking-friendly, Ninja Turtles-themed cash-only Cowabunga bar that sells nothing but booze and popcorn? Ah what the hell, why not. If you don’t like smoke (like myself), there are plenty of other smoke-free bars in which you can find a refreshing ale. When everything is permissible, there’s something for everyone.

Driving tourists through a busy intersection on go-carts? I’ll take illegal in Australia for $100, thanks.

One reason Tokyo can support so many niche businesses is because it’s so dense. And part of why it’s so dense is – because you can just do things – it pulls people in from everywhere.

Agglomeration and network effects compound those forces, and the end result is a city that’s as vibrant as it has ever been—even as much of Japan stagnates. You end up with incredibly rich variety, such as a rickshaw business being run out of a garage, or a button shop beneath an apartment block.

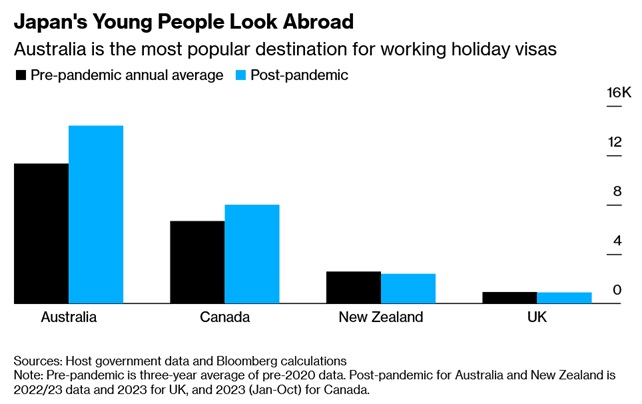

I’m not going to get into all of the details as to why so much of Japan has stagnated while Tokyo has thrived, but the short version is that declining demographics across the country caused the relative returns to investing in the regions to fall faster than in the larger cities, setting in motion something of a vicious cycle that benefitted Tokyo at the expense of everywhere else.

---

After winding through the quiet, inner-city streets of Tokyo for a few hours, I eventually hit the much busier Ueno area. It’s home to a major train station – most shinkansens leave from Tokyo station but swing by Ueno before leaving the metropolitan area – but I didn’t have to walk far to find a hole-in-the-wall ramen joint to stop for lunch.

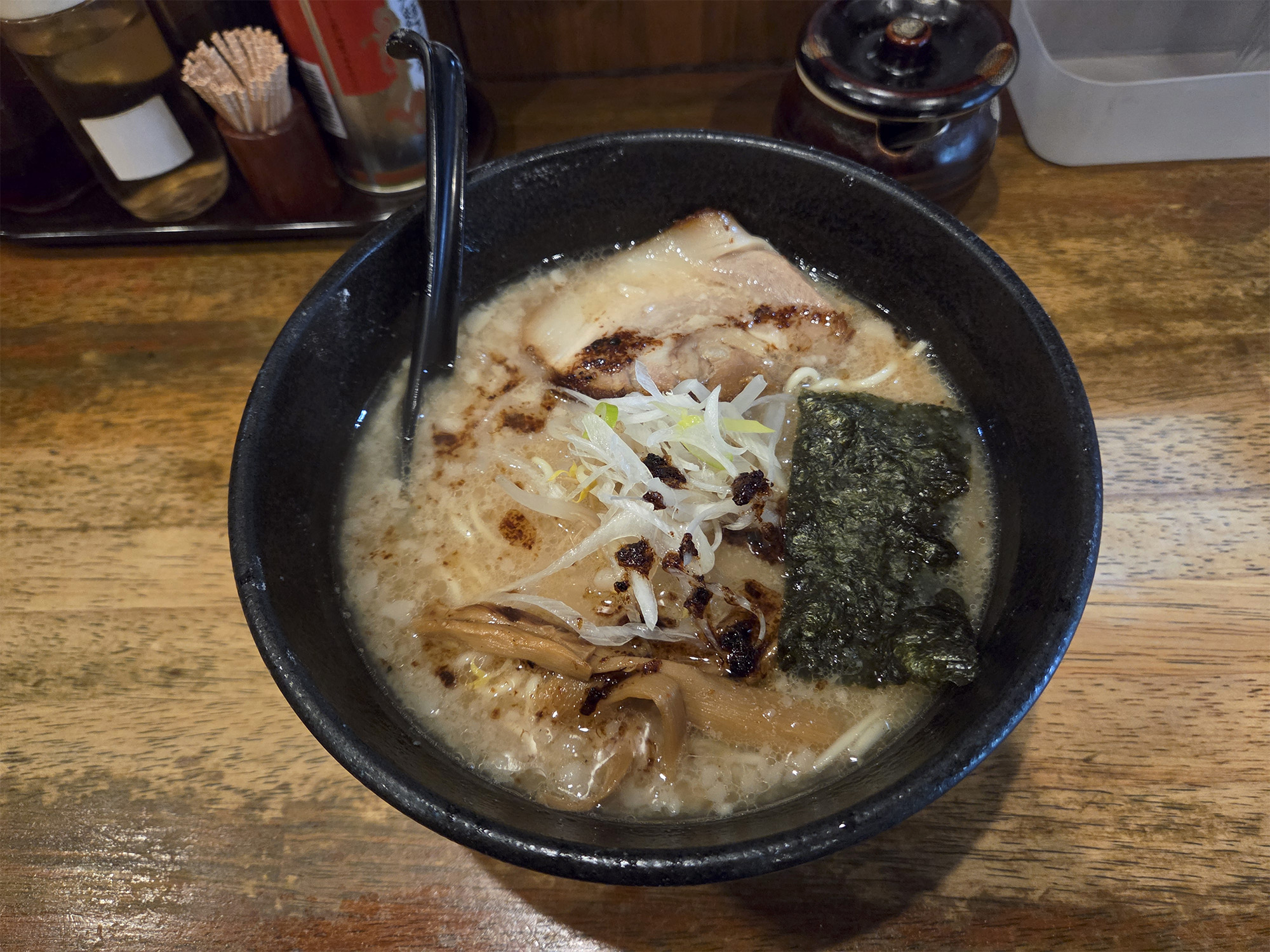

This one in particular ticked several boxes: the tourists exiting Ueno station all walk in the other direction towards the park and zoo, so I figured I was likely to get better value as rents would be lower. Check one. The clientele looked to be almost exclusively Japanese salarymen, and there was no English on any of the signs or menus. Check two.

It was also clear that the shop’s overheads were probably modest; these guys haven’t spent big on décor, and the noodle making machine was literally squeezed into the narrow shop corner. Check three. As for the final check, there was plenty of local competition: it might not have been in Ueno, but it was close enough that there was a plethora of restaurants from which to choose (this joint in particular was sandwiched between a Vietnamese Banh Mi and Indian restaurant).

Needless to say, if you tried to open a similar store in an Australian suburb a few hundred metres away from a major train station you would almost certainly be shut down faster than you can say NIMBY! I ended up paying 750 yen (A$7.50 at the time) for this bowl of tonkotsu-style ramen, which in Australia would probably set you back closer to A$20.

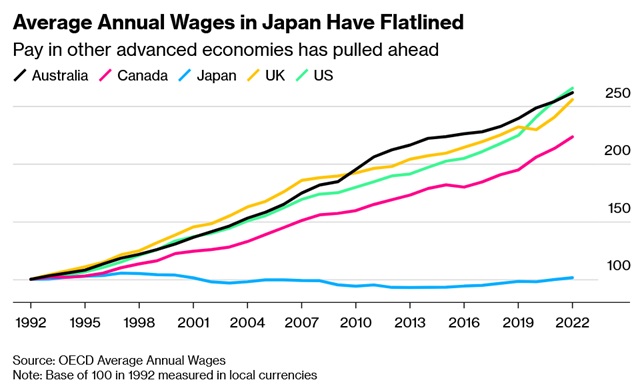

Note that at least some of that price difference is due to the disparity in wages between the two countries – by some measures, average incomes in Australia are nearly double those in Japan – but regulatory barriers matter too.

Such barriers are a reason why even izakayas, Japan’s famously small watering holes, tend to be so large and… sterile when they’re attempted in Australia, completely ruining the experience. In Japan, food safety is treated separately from land use. There are no minimum kitchen size requirements. Restaurants don’t have to provide parking. The lack of such barriers are what makes one- or two-person operations economically possible.

---

In Tokyo, ramen shops – especially the two-person types – are a dime a dozen (although they vary greatly in style). But what I found quite interesting is how location affected prices so much. For example, I took the following pictures outside the exact same ramen franchise, Ippudo, in two different locations. Prices were nearly 10% lower in the venue south of Ueno compared to the one in the more touristy location of Asakusa.

For exactly the same meals!

The Ippudo example was especially revealing, as its Tokyo stores are not franchised but wholly owned by the large Chikaranomoto Holdings, so the differences are almost certainly directly related to costs (probably rent) rather than business decisions by individual stores. If you look closely you’ll notice a few other differences too, such as the use of English on the more expensive Asakusa menu, versus pure Japanese on the cheaper Ueno version.

But even in the same suburb I encountered cases of price discrimination. For example, a shotengai in Asakusa had what I considered quite high prices—a lunch soba set for ¥1,600, for example. While shotengai probably used to be great places to find a meal in Tokyo, these days they tend to be overrun with tourists, so rents and prices have likely risen to match, crowding out the local favourites.

Meanwhile, just down the road at Hoppy street – the namesake of which is a traditional mixed shochu drink – prices seemed a bit more reasonable, with most mains setting you back sub-1,000 yen. While the vendors are probably too small and ‘rustic’ to accommodate the packaged tour groups I try to avoid, it was still brimming with foreigners, likely because of its proximity to Senso-ji and Nakamise. But there were also plenty of locals, and staff trying to lure people into their joints weren’t speaking any English. I took a couple of pictures during both a busy Saturday lunch session and early on a Monday night, and yes, I even tried its namesake drink—Hoppy and shōchū.

It turns out that like a lot of Tokyo, stalls (yatai) such as these emerged organically post-WWII, initially as black markets. They tend to be multi-generational and family-run affairs, have plenty of competition, and presumably don’t pay much in rent despite the location. Rather than shut them down, the government gave them property rights—at least the ones that survived the US occupation, during which many were ordered to be removed.

So, probably worth a shout if you find yourself in the area. If you can’t get out of the touristy areas then I’d definitely go there over some of the restaurants on the main drag, or on one of Asakusa’s shotengai. It’s Japan, so the food is likely to be good everywhere, but there’s just no reason – at least not for mine – to pay overs in exchange for a bit of English on the menu and a five minute walk (Google Translate works very well). Crowds like this full of large, flag-wielding tour groups outside Asakusa’s Kaminari mon are precisely the areas I go out of my way to avoid.

My walks really did help clarify just how much the amount of tourism in an area affects the kind of value (quality/price) that’s available to you. For another example, this Akihabara coffee shop didn’t even bother using Japanese. Welcome to a tourist area! I’m sure the coffee is good, but you’re certainly going to pay for the privilege of enjoying amenities that aren’t likely to be patronised by locals.

Anyway, I’ve got plenty more to write about my walks around Tokyo – including some recent changes and reasons why it doesn’t work so well – but I’m about to get on a shinkansen to Takaoka, so I’ll have to save all of that for part two!