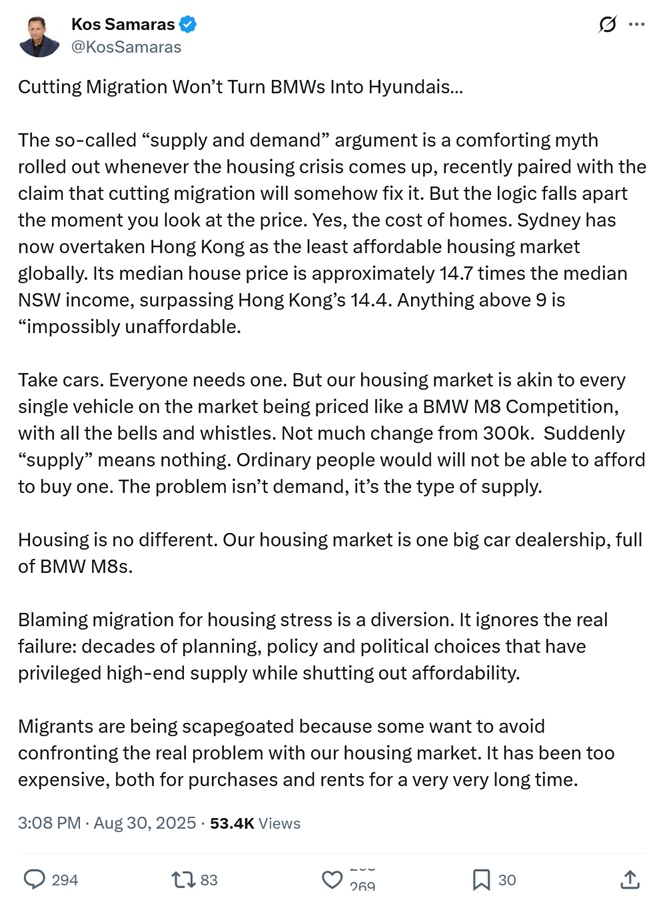

On Saturday I commented on a tweet from pollster Kos Samaras that was misleading at best, downright malicious at worst. But Kos didn’t stop there, penning an even worse tweet on housing that dismissed basic economics as “a comforting myth”:

Other economists described the tweet as “profoundly wrong on almost every level”. But I’m going to go a step further and briefly explain exactly why, because Kos’ mistake is one people frequently make when discussing housing.

The importance of supply#

The market for housing is not one where there’s a monopoly dealership selling only BMW M8s with no substitutes. It’s a spectrum of differentiated goods from detached homes in centrally-located suburbs to apartments out in the sticks.

Prices might be high, but stating that “‘supply’ means nothing” and “ordinary people would will [sic] not be able to afford to buy one” is demonstrably false. The BMW analogy fundamentally misunderstands how housing markets work—unlike cars, housing is a fixed-location asset where new luxury supply directly reduces pressure on existing mid-market stock, improving overall affordability.

Again, all supply is important, whether it’s a BMW or a Hyundai. A market with only new BMW supply is still better for affordability than a market with zero new supply, which is too often the real-world alternative!

The importance of demand#

Kos is correct that it’s wrong to blame migrants for Australia’s relatively high house prices. There are many reasons why housing demand is strong, and migration is just one of them. In fact, it’s a relatively small one, especially given that many migrants are students living in share houses and units near universities, or backpackers in hostels, vans, and dorms out in the regions.

But the claim that “the problem isn’t demand” is demonstrably false. Indeed, the reason houses are increasingly unaffordable is precisely because demand growth has outpaced supply growth. While migration isn’t the root cause, nor even a significant one, at the margin it definitely has an impact on prices.

Likewise, to state that cutting migration “won’t turn BMWs into Hyundais” is also misleading. As I’ve written before, even increasing the stock of luxury housing (“BMWs”) improves affordability across the entire market by reducing the demand pressure on the existing stock of Hyundais.

The supply and demand argument is sound#

Kos is right that blaming migration for Australia’s housing situation is a diversion. But his dismissal of supply and demand leads to equally flawed conclusions.

Demand matters: stopping the flow of migrants would take some pressure off demand, and pretending it wouldn’t does his case a disservice.

Supply matters: you can’t magic up more housing supply tomorrow, but claiming supply growth (even high-end) is irrelevant is equally confused.

The path to housing affordability isn’t choosing between addressing demand (migration) or the type of supply. It’s removing the artificial constraints on total housing supply, regardless of type, that prevent us from building enough homes of all types to meet demand—while preserving the benefits of skilled migration that makes Australians wealthier and better able to afford them.

The real problem isn’t the “so-called ‘supply and demand’ argument” but the refusal by certain political actors to let supply respond to demand. Kos correctly identifies “decades of planning, policy and political choices” as the cause, but misdiagnoses the problem: the issue isn’t too much “high-end supply”, but regulatory constraints that prevent sufficient supply of all types.