Last Sunday, “thousands” of Australians hit the streets across the nation in protest of the current rate of migration. The rally was co-opted by neo-Nazi groups including the National Socialist Network led by Thomas Sewell—a migrant—and they got very chummy with the Katter clan, a dynastic political family for which I have very little regard.

But extremists often co-opt large movements; just the other week, Islamic State terrorists were photographed at the pro-Palestinian protests. Is everyone who attended those a terrorist? Obviously not. Similarly, not everyone who went to the anti-migration rallies is racist or a Nazi. As a general rule, I don’t think we should dismiss what are clearly issues for a lot of people just because a few really bad apples happen to agree with them on that single issue.

And migration is a big issue. While Australia has consistently had world-leading rates and great success with migration, the post-pandemic rebound has clearly upset a lot of people. It seems most folks are comfortable with a migration rate of around 1% of population, but when it gets much above that—let alone doubling!—the influx becomes socially excessive.

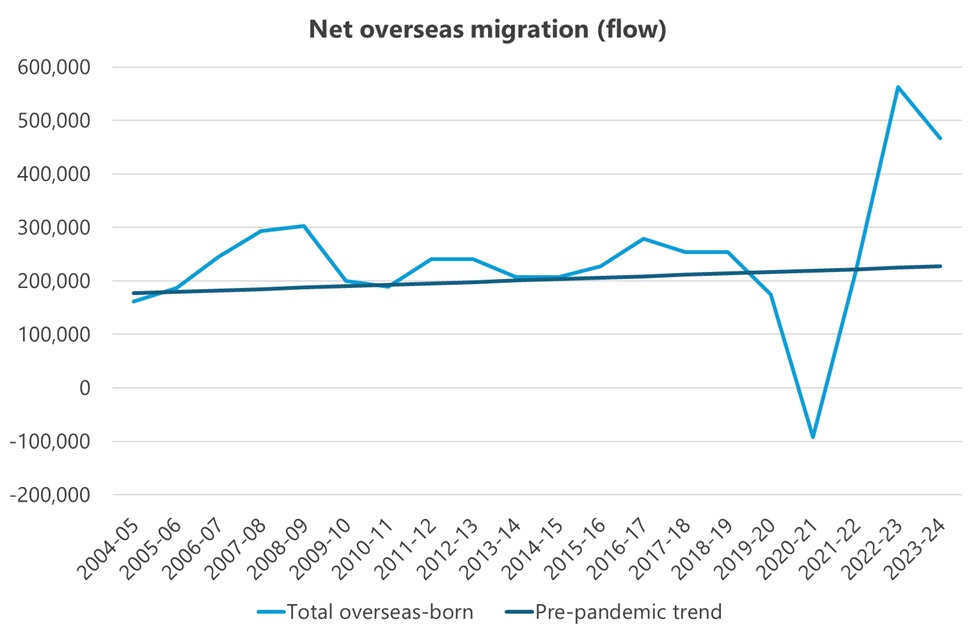

Clearly the pandemic shook things up. The majority of overseas-born migrants are students, only some of whom will stay beyond their studies. But the ‘pause’ in university admissions for a couple of years resulted in a lag: students left each year, but few arrived. Given that a typical undergraduate degree is four years, the data were always going to be distorted for a while.

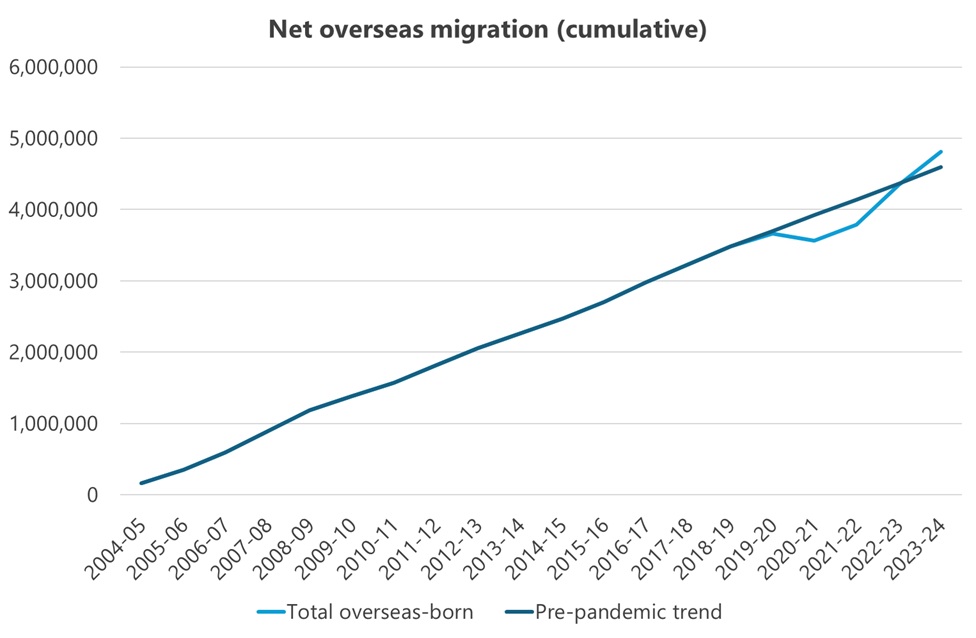

As for the actual numbers, at the end of the last financial year there were cumulatively around 220,000 more overseas-born people in Australia today than there probably would have been if the pre-pandemic trend had continued (first chart above). With a population of approximately 27 million, that’s basically a rounding error—around 0.8% over five years, or 0.16% a year. And according to the government, numbers have come down significantly in 2024-25, although we’ll have to wait for the official figures to know for sure.

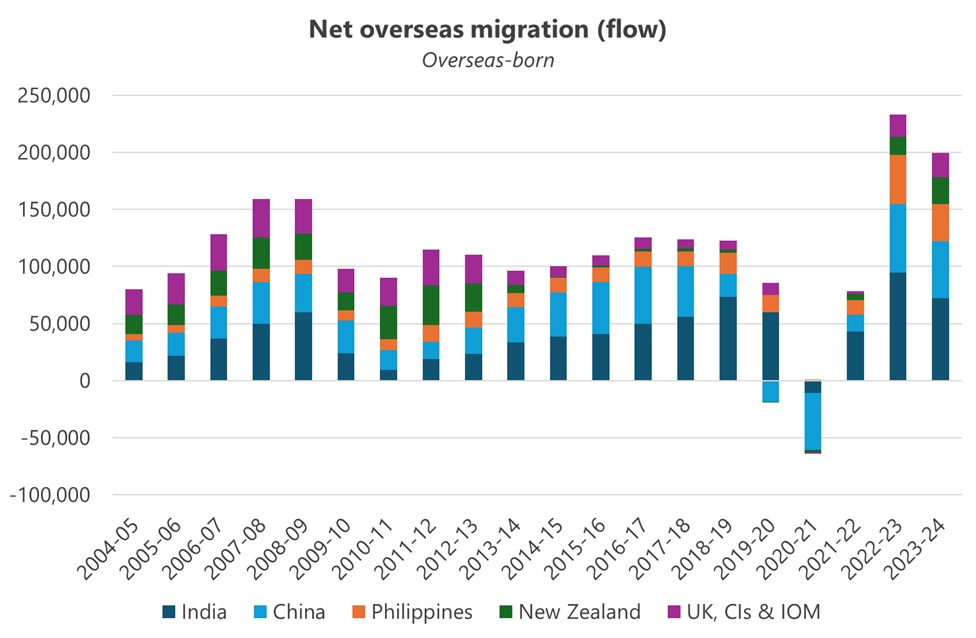

But whether it’s the Trump effect, or the fact that a lot of recent migrants have come from the subcontinent rather than Europe (chart below), the median voter has likely shifted to the right on migration over the past few years.

Even independent senator David Pocock, himself a migrant from Zimbabwe, chirped up the other day:

“One of my frustrations has been that there is a real lack of appetite from the parliament to actually have a debate about this in a sensible way, and then come up with a plan when it comes to migration and population that actually wards off some of the feelings of ‘well, there is no plan’.”

Pocock raises a valid concern. The government does have a ‘population plan’, although it’s conspicuously light on hard numbers—which is perhaps why it renamed it to the ‘population statement’ last year! If the Albanese government wants to help keep emotions in check, giving that report some extra attention this year might be a good first step.

But Pocock also raises a deeper issue: what is the right amount of migration? Some economists, most notably Bryan Caplan, take a moral and efficiency approach: the global economic gains far outweigh the costs to destination countries, therefore we should have open borders.

Bryan is of course technically correct, but policy in a democracy isn’t determined on moral or pure efficiency grounds. Those political constraints mean an increase in migration (which Bryan would favour) might actually reduce migration in the long-run.

Essentially, if voters perceive the rate of migration to be too high, lacking in detail, or visibly straining infrastructure, then the marginal voter will shift towards a more Trumpian, populist position on immigration. In Australia, that would give ammunition to the likes of Bob Katter, resulting in voters electing more of his ilk. Eventually, a small coalition of them could end up as Kingmakers in a tight parliament, resulting in a drastically lower rate of migration—an outcome that would be unequivocally bad for Australia (and the world) in the long-run.

Those political constraints mean some kind of limit on migration is needed (I’d prefer using fees over quotas), and given the fever-pitch of last Sunday’s rallies, the Albanese government must get serious about it. Basically, it needs to heed Pocock’s advice and come up with a well-communicated, public plan. Not just for migration numbers, but also how it plans to solve the various government failures that helped fuel the discontent: zoning restrictions inflating housing costs, under-policing straining law and order, and inadequate infrastructure investment reducing people’s quality of life. Without reforms in those areas, even modest migration flows will feel unsustainable to many.

But words alone won’t cut it. The Albanese government also needs to bring the net overseas migration figures down to somewhere close to pre-pandemic levels—or perhaps even a bit lower—this year or next. If it fails on either front, the populist, anti-migration movement will grow stronger, win more political leverage, and eventually lock in a far lower rate of migration. That would mean less prosperity, weaker institutions, and diminished geopolitical influence for what will be a smaller, older future Australia.