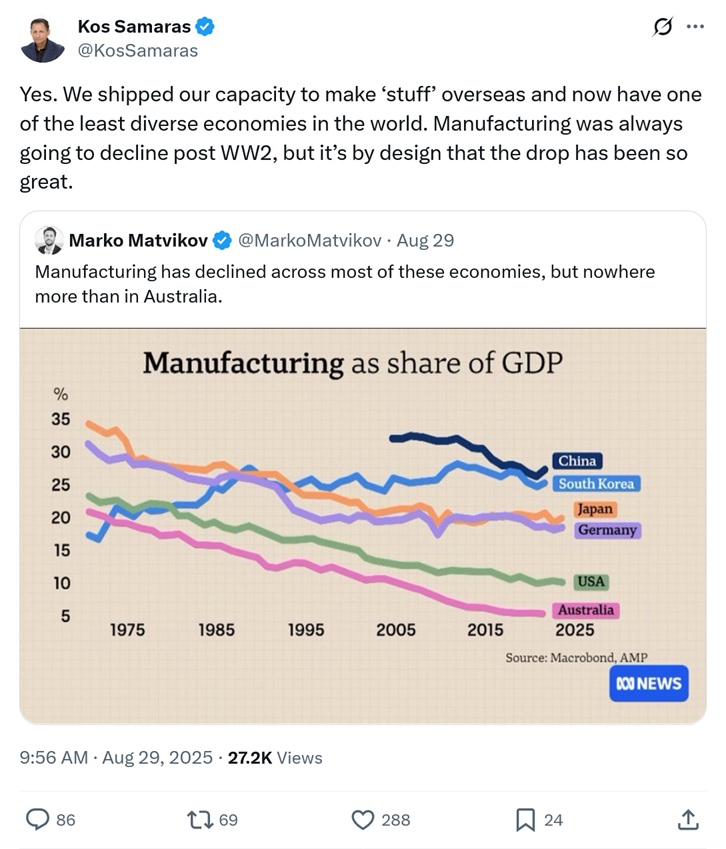

If there’s one line I read on social media more than anything—other than “immigrants bad!”, of course—it’s that Australia doesn’t make ‘stuff’ anymore. For example, on Friday pollster Kos Samaras tweeted the following:

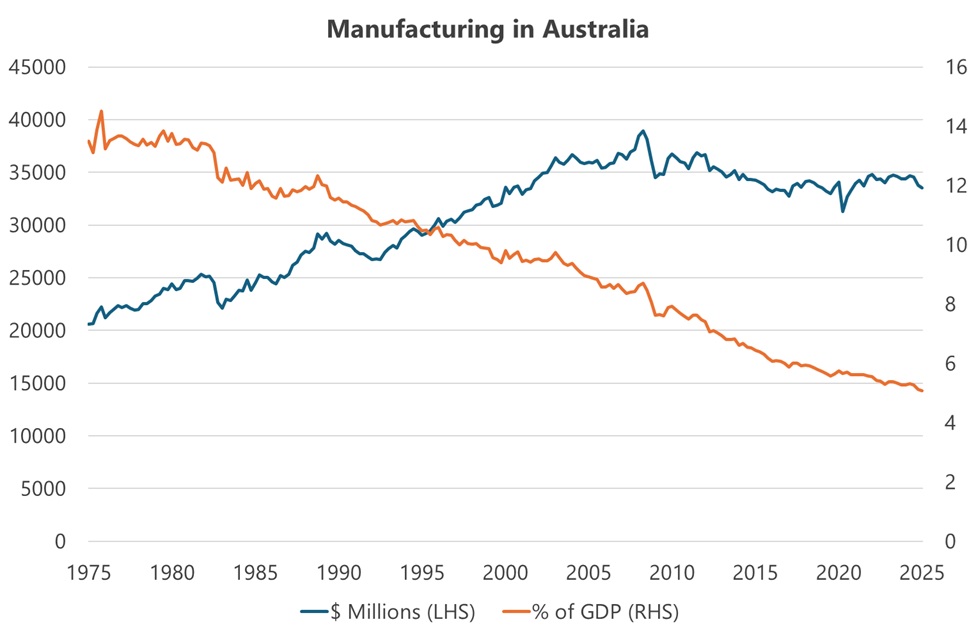

It’s true that Australia’s manufacturing sector, which has always been comparatively small, has shrunk as a share of GDP since the 1970s. But that’s largely because the GDP produced by other sectors has gone gangbusters. In absolute terms, we actually still manufacture a lot of ‘stuff’ in Australia:

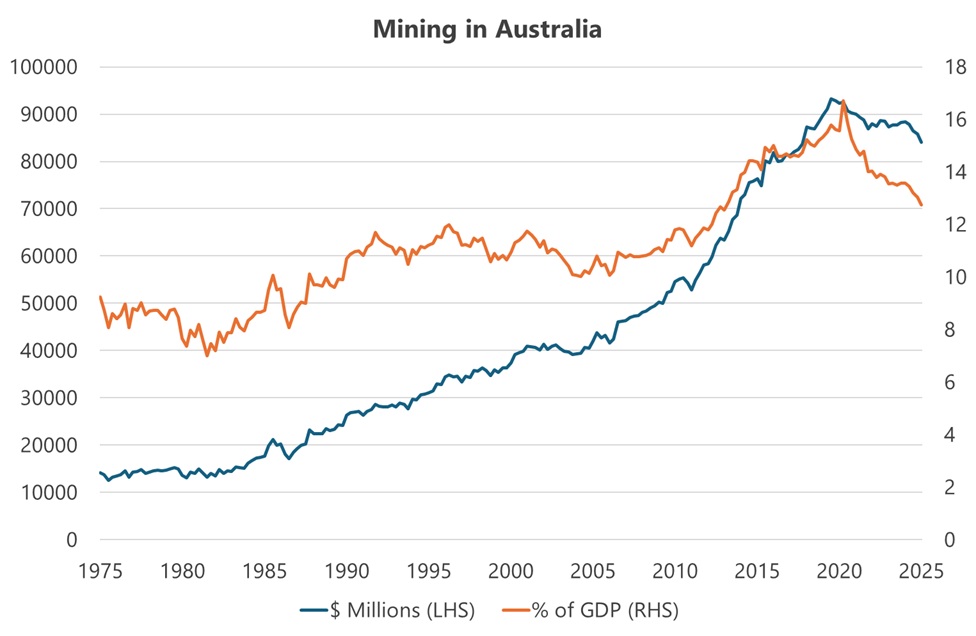

There has been no ‘hollowing out’ of Australia’s industrial base. It’s just that instead of continuing to expand the manufacturing sector, Australians have allocated resources where the returns are greater. One of those sectors is mining, whose share of GDP has gone from around 8% in the 1970s to 13% today—filling a good part of the share of GDP that manufacturing vacated:

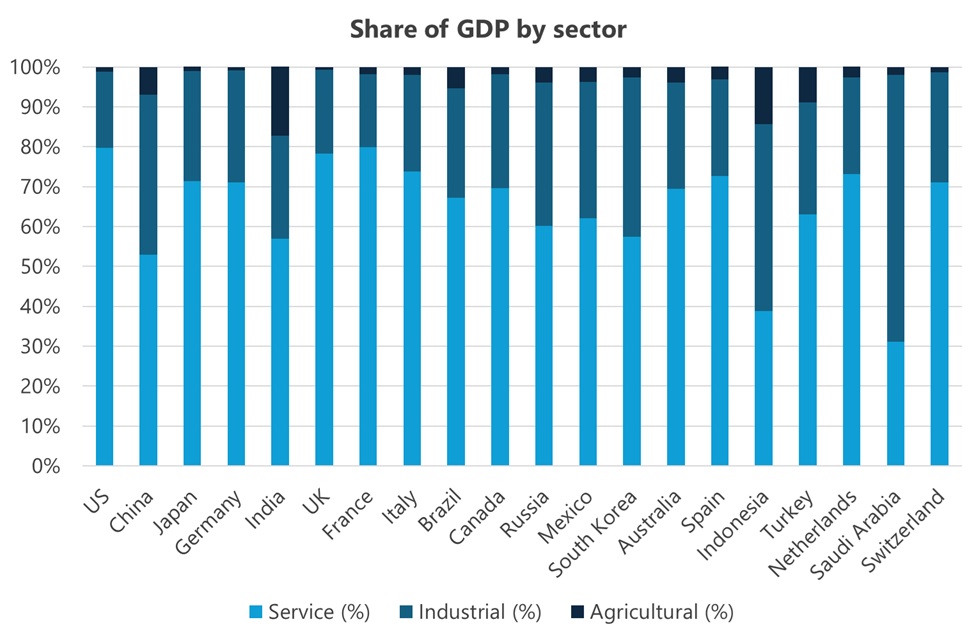

The other sector that has grown in relative size is services, which now makes up around 70% of the Australian economy—and much more than that in terms of employment. For context, Australia’s services share is actually below the levels seen in most similarly-wealthy nations. Indeed, “industry” as a share of the Australian economy is in-line with Japan and Germany, and well ahead of the US and UK:

By definition, if you want to manufacture more ‘stuff’ in Australia as a share of GDP, you must reduce the share of another sector where resources are currently being allocated according to consumer preferences. Doing so will make most Australians worse off because it will reduce productivity by requiring higher-cost resources to make the goods, rather than just importing them and letting Australians do what they’re best at (creating a deadweight loss).

Economists call that comparative advantage, a concept the great Paul Samuelson described as both “logically true” and “not trivial”:

“…attested by the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to grasp the doctrine for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to them.”

I think the renewed fetishisation of manufacturing in Australia—and elsewhere, as its roots come from the Trumpian MAGA faction in the US—is a dangerous movement. It misunderstands how modern economies work, and will cause immense damage as it seeks to restore an era that simply won’t return no matter how hard they push on that particular string.

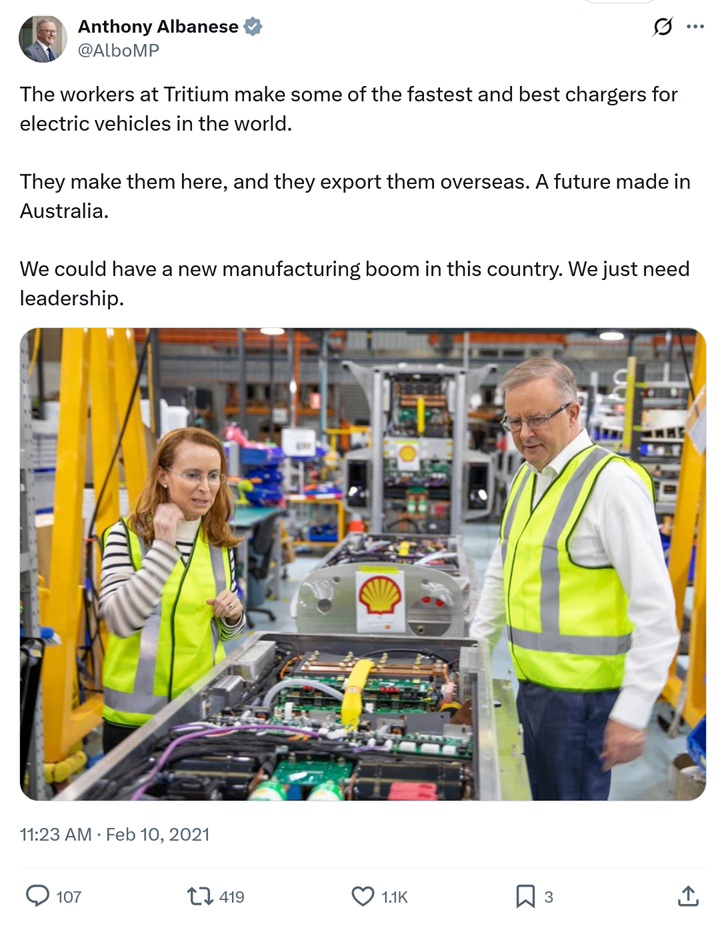

Unfortunately, in Australia the movement has a strong ally in its “important and intelligent” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who has been dutifully acting as chief cheerleader of Australia’s manufacturing fetishisation under the banner of a Future Made in Australia:

For reference, Tritium took the money and ran to the US, only to enter insolvency and eventually get bought by Indian manufacturer Exicom. Its electric vehicle chargers were so bad that local governments are now ripping them out rather than try to constantly repair them.

Such is the nature of industrial policy—politicians lack both the knowledge and the incentives to efficiently allocate resources, and so they end up picking losers just as often as they pick winners.

The fact is, unless the government reduces the relative returns to other industries such as mining and services, for example through protectionist policies like tariffs and quotas,1 then restoring manufacturing’s share of GDP in Australia will require open-ended, ever-expanding subsidies.

That is what a future made in Australia looks like. And if the government truly acts on it, it will suffocate our most productive industries and make us all significantly poorer.

Is that really what people like Kos Samaras want?

#1 To be perfectly clear, I do not endorse such proposals. I’m simply stating what it would take to use policy to achieve the stated goal of growing manufacturing as a share of GDP.